When Sam & Dave, the classic ’60s soul group, performed their signature hit, “Soul Man,” I wonder how they felt about the Blowfly parody “Hole Man” and if they were proud about it. What about the artists whose original tunes inspired “Y.M.C.(G.)A.(Y.)” or “Shittin’ on the Dock of the Bay”?

Because I definitely would be proud of it … even though I’d sheepishly look down at my feet in total shame and absolute guilt.

I learned of those songs when I discovered Blowfly. When I was a somewhat nerdy, yet eclectic teenager, I was on way to a school marching band competition. Somewhere in the middle of rural Oklahoma, the bus made a roadside stop for bathroom breaks and caffeinated drinks.

I noticed a rack of outré music journals, cult movie zines and, of course, thoroughly profane Mexican nudie mags. All I had was $20 for lunch, but I bought $19 worth of the strange magazines and a liter of Diet Dr Pepper with the change. Oh, yeah!

The music magazine — sorry, I can’t remember the name — had articles about Doug Sahm, Lou Reed and, more importantly, Blowfly (aka Clarence Reid). Reading, learning and wanting to know more about the nastiest rapper, I was heterosexually enamored.

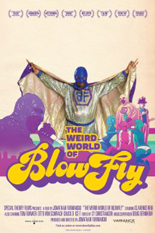

Since then, I’ve encounter him and his music in the most prurient of places — such as a dying record store in San Antonio, a flea market in New York City or a beer-stained trash can in Fort Collins, Colorado, to be sure — all leading to the 2010 film The Weird World of Blowfly.

Although Blowfly died in 2016, this documentary — a cock-umentary, if you will — finds him in the middle of his ill-advised comeback tour. With his history of party records in tow and the help of manager Tom Bowker, he’s trying to make a comeback, but, at 70, it’s harder than it sounds.

Sadly, he’s playing to lackluster crowds in small clubs and, worse, the worst crowds somewhere in Europe. Through the film, we find out that his royalties are gone, he needs surgery on his leg, and, most of all, people have been flatulent on his backstage pizza.

A demented genius, a warped personality and a hyper-sexed fuck demon: This is the Blowfly persona. Yet we instead finding him reading the Bible with his aged mother, goofing around with Bowker’s pre-teen daughter and having a midnight snack of McDonald’s hash browns with ample amounts of ketchup and maple syrup.

I never knew about the two conflicting sides of this man, but talking heads like Ice-T, Chuck D and other performers pay tribute, making sure he stayed a dirty secret in your dad’s party records. To be fair, the greatest tribute comes from Bowker when a slick hipster decries Blowfly, upon which the manager truly castigates, denigrates and dominates the hipster in his own personal hell.

Whether you’ve been taken by “Hole Man” or another one of Blowfly’s infamous bits of wordplay surrounding comically slick crevices, gaping love holes and other places to stick your wanton meat stick, The Weird World of Blowfly is the perfect condom to the real-life cultish career. —Louis Fowler

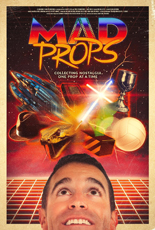

Danger, romance and seduction: the holy trinity of a now-extinct film subgenre that kept beautiful, busty women named Shannon employed for the better part of the 1990s. Besides the obvious visual attributes, what made those flicks tick? Where did they come from? More importantly, why did they disappear?

Danger, romance and seduction: the holy trinity of a now-extinct film subgenre that kept beautiful, busty women named Shannon employed for the better part of the 1990s. Besides the obvious visual attributes, what made those flicks tick? Where did they come from? More importantly, why did they disappear?