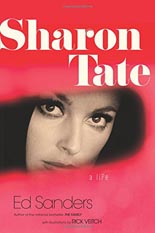

Like its subject, Sharon Tate: A Life debuts with much promise before things go south. In Tate’s case, it wasn’t her fault; in counterculture icon Ed Sanders’ book, the fault is all his.

Like its subject, Sharon Tate: A Life debuts with much promise before things go south. In Tate’s case, it wasn’t her fault; in counterculture icon Ed Sanders’ book, the fault is all his.

Since the Valley of the Dolls star died so young — at age 26, slaughtered in the murder spree of Charles Manson’s “Family” in the summer of ’69 — her life story prior to marrying enfant terrible director Roman Polanski (Rosemary’s Baby) is hardly household knowledge. It’s a largely charmed existence from loving military family to accidental model-cum-actress — a woman who, despite incredible beauty, was less interested in the world of glitz and glamour in which she found herself than settling down and raising a family.

Sharing that anti-Hollywood story is why Sanders’ biography starts strong, even considering his penchant for the hyperbolic; many a sentence begins carrying the weight of overimportance, e.g. “The Fates had their say …” Clearly, his writing voice is a unique one, given to spontaneity and whimsy, such as his freewheeling description of Polanksi, “obviously propelling himself Up Up Up. … He could Get It Done! He was a picture-per-year triumph.” It begins to work against Sanders, though, especially with his habit of sporadically repeating one particular thought/sentence throughout the text:

• “The past is like quicksand,”

• “The past — often like quicksand,”

• “The past can be like quicksand,”

• “Quicksand of the past”

• and, in eventual shorthand, “Quicksand.”

We get it.

Larger cracks in the narrative appear earlier, in the form of needless tangents. For instance, it’s one thing to discuss Tate’s audition for the classic movie musical The Sound of Music, as that was something I did not know. But since she didn’t get it, what point is there is then diving into a couple paragraphs of plot synopsis, complete with mentions of the performers who were cast, not just in Tate’s role but all the other major parts?

Even a film in which Tate did star in, Polanski’s 1967 horror comedy, The Fearless Vampire Killers, why devote several pages going through its plot, scene by scene, beat by beat? It’s almost as if Sanders wants us to know that he actually did his research — something readers automatically assume of nonfiction. He tells us anyway: “In the course of writing this book, I watched a DVD of Fearless Vampire Killers …” I should hope so!

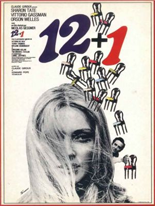

And then there’s the curious case of 1969’s The Thirteen Chairs (aka 12+1), a forgotten Italian farce in which Tate starred opposite Vittorio Gassman. Sanders again gives us a full synopsis, but what sticks out this time around is … well, just read this two-paragraph excerpt first …

And then there’s the curious case of 1969’s The Thirteen Chairs (aka 12+1), a forgotten Italian farce in which Tate starred opposite Vittorio Gassman. Sanders again gives us a full synopsis, but what sticks out this time around is … well, just read this two-paragraph excerpt first …

Sharon and Gassman track the chairs to Paris and then to Rome. They run into an assortment of unusual characters, among them a driver of a furniture moving van named Albert (Terry-Thomas), a prostitute named Judy (Mylène Demongeot), the head of a roaming theater company that stages a strange version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Orson Welles), the Italian entrepreneur Carlo Di Seta (Vittorio De Sica), and his curvy daughter Stefanella (Ottavia Piccolo.) [sic]

The chase for the jewels concludes in Rome, where the chair containing the treasure finds its way into a truck, and is collected by nuns who auction it off for charity. With nothing much left to do as a result of the failure of his quest, Mario travels back to New York City by ship, as Pat/Sharon sees him off and waves goodbye to him.

… and now compare what you just read to the summary on the film’s Wikipedia page:

… the two then set out on a bizarre quest to track down the chairs that takes them from London to Paris and to Rome. Along the way, they meet a bunch of equally bizarre characters, including the driver of a furniture moving van named Albert (Terry-Thomas); a prostitute named Judy (Mylène Demongeot); Maurice (Orson Welles), the leader of a traveling theater company that stages a poor version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; the Italian entrepreneur Carlo Di Seta (Vittorio De Sica); and his vivacious daughter Stefanella (Ottavia Piccolo).

The bizarre chase ends in Rome, where the chair containing the money finds its way into a truck and is collected by nuns who auction it off to charity. With nothing much left to do as a result of the failure of his quest, Mario travels back to New York City by ship as Pat sees him off and waves goodbye to him.

Hmmm.

These off-course flights happen regularly, putting Sharon’s life story on hold to a point that the reader wonders if Sanders forgot about whom he was writing. Most egregious is the procedural account of Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination, tying Tate to a conspiracy theory — one of several (another being an underground sex-film ring) that Sanders never quite knots.

With its last third, Sharon Tate: A Life ceases being even moderately compelling, giving itself over to rehashing the misdeeds of the Manson Family — not just the grisly slayings of That August Night, but in general; all of that, of course, is material well-trod before, from Vincent Bugliosi’s seminal Helter Skelter to Sanders’ own acclaimed book on the topic, 1971’s The Family.

Photographs related to the Manson Family’s carnage pepper these pages, but oddly, don’t seek pictures of Tate. Instead, Sanders has commissioned the highly talented comic book artist Rick Veitch (Swamp Thing) to provide illustrations. This creative choice would be more welcome if it didn’t leave such a bitter aftertaste; Veitch’s last drawing depicts Sharon and unborn child in heaven, hovering over her gravestone, in a classless manner that suggests you could purchase a velvet painting of it from a dude in a van parked in the lot of that abandoned gas station on the corner. Sanders himself contributes to that ill feeling by closing the book with a poem from his own pen, reading in part:

O Sharon

Your son’d be

what

well into his 40s by now

& you’d be

if still acting

playing comedic grandmother roles

Quicksand. —Rod Lott