I turned in 69 graphics to potentially use in my new book, Mars in the Movies: A History; the publisher used 43. My previous Guest List for Flick Attack shared 13 that sadly didn’t make that cut, mainly due to resolution concerns. Here are 11 more, kicked back mainly for the same reason. However, unlike the last batch, it is probably just as well that these were not used, as nearly all are not as clearly focused on Mars as the ones that did get printed in the book.

I turned in 69 graphics to potentially use in my new book, Mars in the Movies: A History; the publisher used 43. My previous Guest List for Flick Attack shared 13 that sadly didn’t make that cut, mainly due to resolution concerns. Here are 11 more, kicked back mainly for the same reason. However, unlike the last batch, it is probably just as well that these were not used, as nearly all are not as clearly focused on Mars as the ones that did get printed in the book.

1. From the 1918 Danish film A Trip to Mars (Das Himmelskibet). Unavoidably blurry, once the spaceship Excelsior lands on Mars (see my previous Guest List) and the crew emerges, they are fêted by throngs of happy Martians. The costuming and production design are impressive.

2. From the USSR’s lavish Aelita, Queen of Mars (1924), again, unavoidably blurry. Shown with its inventor, these triangles comprise a Martian telescope that Aelita uses to focus on earthman Lor, with whom she falls in love. I am enamored of the idea of using plastic triangles to create a working telescope!

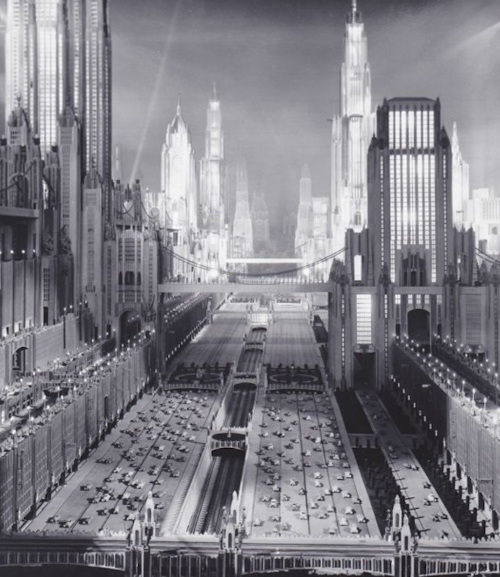

3. Regarding the one-and-only Mars talkie released between 1924 and 1938, Just Imagine (1930), American musical authority Miles Kreuger reports in The Movie Musical from Vitaphone to 42nd Street: “[Just Imagine’s] massive, distinctive Art Deco cityscape was built in a former Army balloon hangar by a team of 205 technicians over a five-month period. The giant miniature cost $168,000 to build and was wired with 15,000 miniature lightbulbs.”

4. The Oct. 30, 1938, CBS Mercury Theater on the Air Radio-Play stirred things up a bit. This was just days after Nazi Germany marched into the Sudetenland area of Czechoslovakia (that would be like Canada sending armed troops and tanks into Washington state and Oregon, and claiming them as part of Canada!). As a result of elevated tensions all around the globe, when much of America turned on their radios and heard cleverly produced pseudo-news announcements claiming that Mars was invading earth, combined with the sounds of battle and panic, thousands panicked. Already fraught with submerged anxiety as they watched “in real time” Europe collapse, listeners assumed that the invasion from Mars was all too real, frantically warning family and friends. It was a phenomenon of mass delusion that lasted perhaps 90 minutes or two hours at the most. The panic was the result of a pre-Citizen Kane Orson Welles and his Mercury Theater on the Air performing on CBS radio their re-imagined version of a classic piece of literature just as they did every week. In fact, just the week before they’d presented Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days and the week before that Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Immortal Sherlock Holmes. On this night, the night before Halloween 1938, they performed H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds in an updated format that imitated intense news bulletins coming from Grovers Mill, New Jersey. In fact, most of the show’s audience had actually switched over from a boring segment on the more popular program The Chase and Sanborn Hour featuring Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, thereby missing the show’s opening disclaimer. Howard Koch, who wrote The War of the Worlds radio script for the broadcast, says in his book, The Panic Broadcast, that the show “caused the submerged anxieties of tens of thousands of Americans to surface and coalesce in a flood of terror that swept the country.”

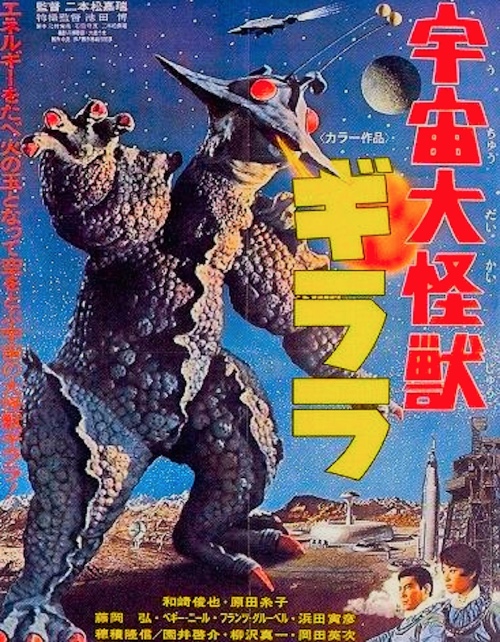

5. The monster scenes in The X from Outer Space (1967) are of the standard man-in-a-suit/creature-on-the-loose-demolishing-buildings sort. That said, the film is chockfull of interesting space vehicles blasting through space, and there is an elaborate, Moon-based spaceport model that is a joy to behold. Besides, I am an unabashed Japanese monster fan! That the space expedition never did get to Mars seems a small point.

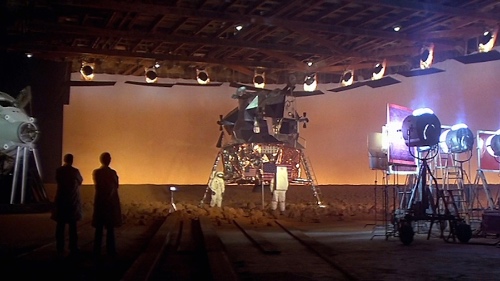

6. The conceit of Peter Hyams’ Capricorn One (1978) is that in the near future, NASA fakes a manned Mars landing by using Hollywood’s tricks of the trade, sets and special effects, but when things really go south, the agency tries to kill the three astronauts.

7. A John Carter (2012) IMAX 3-D poster. The 3-D experience of this film is special. (Copyright © Walt Disney Pictures)

8. Only five years after his debut, Marvin the Martian co-starred with Daffy Duck and Porky Pig in Duck Dodgers in the 24 1/2th Century (1953). George Lucas loved this cartoon so much that he specified that it should be shown with the 1977 Star Wars whenever possible. Warner Bros. animator Chuck Jones remembers in a CartoonResearch.com interview, “Lucas said that he saw Duck Dodgers the year it came out, when he was eight years old and he said that it impressed him so much that he decided he wanted to make movies.”

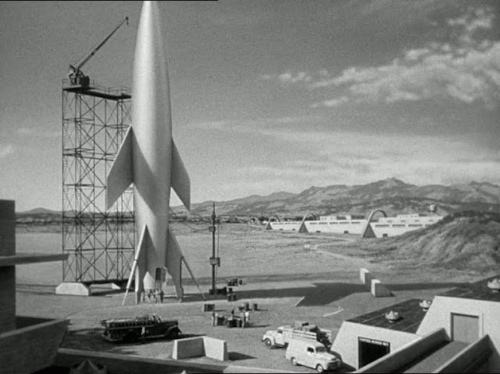

9. Universal Pictures used matte paintings extensively in its low-budget sci-fi films of the 1950s. This matte painting from Abbott and Costello Go to Mars (1953) of the picture’s rocket on its launching pad gives the film a feel far more expensive than it really was. In fact, Abbott and Costello Go to Mars was graced with several handsome matte paintings.

10. In my book Mars in the Movies, there is a discussion of The Angry Red Planet (1959) and of the Cinemagic process in which much of the picture was filmed. Cinemagic was the brainchild of Norman Maurer. In fact, the results that appeared in the finished movie on the big screen were not what Maurer had intended. In order to realize his vision, he would have needed to work with film lab technicians through trial and error to correct the images. But the production ran out of time and money, and there was no choice but to release the picture in a compromised state.

Later in The Three Stooges in Orbit (1962), which he produced, Maurer was able to successfully show, albeit in a very abbreviated version and in black and white, what he had hoped to achieve with Cinemagic. The clear potential is very interesting. The actors in both movies needed to be filmed in high-contrast, so their costumes and makeup could only be black and white. Here we see the Stooges on set in makeup (left) and the final processed Cinemagic image (right) with a cartoon effect. The sequence in the film was only a couple of minutes long and was shown on a TV set. Nonetheless, this had been the original concept for The Angry Red Planet, though within a bright red setting.

11. When director Byron Haskin gathered his team in Death Valley to begin filming Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964), he made a supremely clever discovery. The pure brilliant blue skies visible over the mountains and desert were a perfect natural blue screen, and he used this fortuitous discovery to insert the film’s red skies, one of the high points of the movie. Here is a scene around dusk; we see the fading red sky and the growing night, not to mention three alien craft borrowed incongruously from Haskin’s earlier film The War of the Worlds (1953). —Thomas Kent Miller