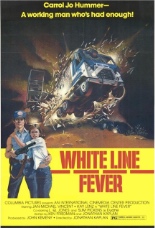

Apologies to Jonathan Kaplan’s White Line Fever and its star, Jan-Michael Vincent, for wrongly assuming all these years that it was a film about cocaine. Sometimes the private demons of public figures can cause one’s mind to mix fact with fiction. (Submitted for my defense: that title, c’mon!)

Apologies to Jonathan Kaplan’s White Line Fever and its star, Jan-Michael Vincent, for wrongly assuming all these years that it was a film about cocaine. Sometimes the private demons of public figures can cause one’s mind to mix fact with fiction. (Submitted for my defense: that title, c’mon!)

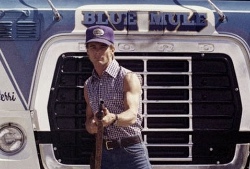

Instead, the actioner — one of many hick flicks at the time to cast the CB-clutching working man as an American hero — concerns itself with corruption in the trucking industry. The character played by Vincent (1972’s The Mechanic) may sport a feminine-sounding name, but Carrol Jo Hummer is masculinity embodied: a war veteran, a Southerner, a family man, a blue-collar clock puncher. Returning from Vietnam to his Arizona home and his soon-to-be bride (Kay Lenz, 1985’s House), Hummer happily puts himself in debt “up the wazoo” to buy a rig and pursue his late father’s independent-trucking dreams. Dubbing his bucket the “Blue Mule,” Hummer brims with Brut-splashed zeal at the prospect of hitting the highway for an honest day’s pay.

His first stop is to see his pappy’s former partner (Slim Pickens, Sam Peckinpah’s The Getaway), who works for a shipping biz run by the greasy, sleazy, sexist and racist Buck (L.Q. Jones, The Brotherhood of Satan). Hummer immediately gets work, but when he sees illegal slot machines and smokes being loaded into his rig, he refuses. While it’s the right thing to do, it’s the wrong decision in the beady eyes of Buck, who gets Hummer blackballed all over town. With a two-grand monthly payment to the bank weighing down his shoulders, but unable to make a haul, Hummer has no choice but to get even, and that requires getting his mitts dirty.

His first stop is to see his pappy’s former partner (Slim Pickens, Sam Peckinpah’s The Getaway), who works for a shipping biz run by the greasy, sleazy, sexist and racist Buck (L.Q. Jones, The Brotherhood of Satan). Hummer immediately gets work, but when he sees illegal slot machines and smokes being loaded into his rig, he refuses. While it’s the right thing to do, it’s the wrong decision in the beady eyes of Buck, who gets Hummer blackballed all over town. With a two-grand monthly payment to the bank weighing down his shoulders, but unable to make a haul, Hummer has no choice but to get even, and that requires getting his mitts dirty.

White Line Fever skillfully follows the Walking Tall template of rural revenge to appease audience expectations and to elevate Hummer to that rarified status of folk hero for the common man. (But to speak of the common woman for a moment, Lenz shines with good-natured grace and power in the first half, before a lazy soap-opera subplot tosses her character into the backseat.) The movie’s iconic, climactic shot of the Blue Mule crashing through the logo signage of the conveniently named Glass House represents an extended middle finger to corporate America and all its malfeasance.

I’m guessing Kaplan drew upon his education through the Roger Corman school of directing (Night Call Nurses) when he chose to shoot that stunt in slow motion, because that’s just the kind of thing the legendary producer would advise his students to do with their films’ visual orgasm: Put it all up on the screen. Technically, Fever is not a Corman picture, yet it operates in the same efficient manner as much of the man’s low-budget fare of that time: with more going on underneath its boom-boom-pow surface. —Rod Lott